Documentary is a filmmaking method inherently designed for remembrance. In truth, it’s the method that almost all carefully could be aligned with images and the need to seize a second, an individual, or a factor earlier than the forces of time overcome and erase its existence. So, you already know, often with these movies, you’re going to get a subject of some import. The three movies on this Chicago Worldwide Movie Competition dispatch take the shape’s potential to coronary heart in a bid to protect the recollections of a Kosovo village, the legacy of a disgraced Ghanaian president, and an space of Italy beforehand worn out by a volcano. These movies, to various levels of success, stand as a testomony to the significance of remembrance, even when the recollections damage.

For the final yr or so, cinema has been inundated with movies about unmoored people and shaken communities grappling with the lack of their homelands. Swiss-Albanian director Dea Gjinovci’s elegiac documentary “The Fantastic thing about the Donkey” is a fantastic addition to that development. It considerations the filmmaker’s father, who, along with his daughter, returns to their small village in Kosovo for the primary time in almost 60 years. Whereas there, her father, Asllan, shares recollections that Gjinovci decides to stage as summary theatrical productions, bringing the previous again to modernity with efficiency.

That is additionally a movie that mixes politics with loss. In 1968, a 19-year-old Asllan was a political activist when he was exiled. Upon leaving the nation, he misplaced contact along with his household, notably his mom, whose demise has at all times lived in household lore. Asllan shares the oppression his household suffered below Serbian authorities and the dangers taken to fight their rule with gorgeous readability; he additionally investigates his mom’s demise with equal fervor. These household tales, after all, impression Gjinovci as effectively. As a result of she grew up in Switzerland, she’s by no means seen her father’s homeland. Within the opening sequence, when Asllan emerges from the woods, strolling towards the sphere the place his stone residence as soon as stood, within the assuredness of her lens you’ll be able to really feel the haunting reverence Gjinovci has for this second.

Regardless of the movie’s fanciful title, nevertheless, there aren’t many donkeys on this image. Two scenes that includes donkeys bookend the work, and when you can actually sense how the animal traces again to a second of innocence in Asllan’s life and serves as a reminder of his personal endurance, the moments don’t cohere sufficient to be the movie’s throughline. As an alternative the movie is strongest when it doesn’t give option to twee metaphorical scenes, however focuses on the cathartic reclamation of 1’s historical past.

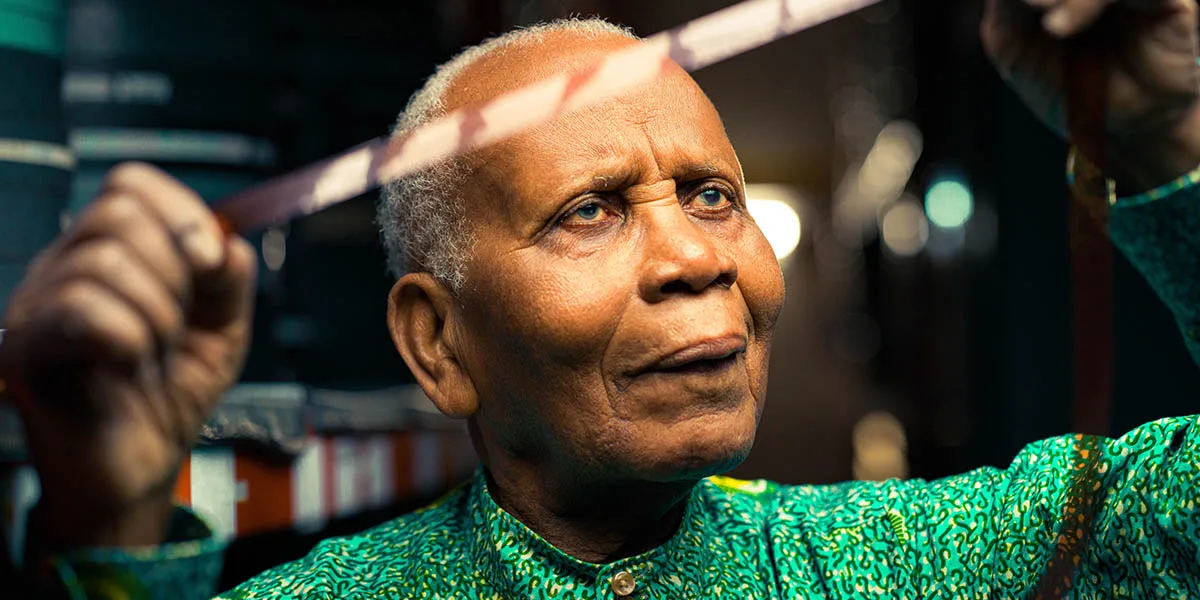

I actually want director Ben Proudfoot’s messy historic documentary “The Eyes of Ghana,” a partial product of government producers Michelle and Barack Obama’s Greater Floor Productions, have been higher. It’s a type of movies whose need to inform a little-known story grants it some slack, however whose unsteady execution rapidly evaporates a lot of the goodwill you got here into it with. The movie considerations legendary Ghanaian cinematographer and director Chris Hesse’s need to reclaim over a thousand cans of footage from London that he shot of the nation’s first president Kwame Nkrumah earlier than the chief’s downfall from a navy coup in 1966. Whereas that story alone would make for an unbelievable documentary, Proudfoot overpacks “The Eyes of Ghana” with far too many different threads for all of it to carry collectively.

Proudfoot is a two-time winner of the Academy Award for Finest Documentary Brief Movie (“The Final Restore,” “The Queen of Basketball”), a background you’ll be able to sadly really feel when “The Eyes of Ghana” begins with the three chilly opens. The primary opener introduces Hesse; the second produces his protege, director Anita Afonu; the third brings within the steadfast projectionist of Ghana’s Rex Cinema, Addo, who usually desires of internet hosting movie on the disused film home once more. With that set-up you’ll be able to just about guess the place this movie will find yourself. However, Proudfoot doesn’t neatly interweave these threads. He continues shifting topics, giving us the early historical past of Ghanaian moviemaking, Nkrumah’s troubled story, and the way America disrupted the Pan-Africa motion by way of destabilizing newly impartial governments. Slightly than making a coherent function out of those various matters, sadly, Proudfoot has produced a number of shorts whose whole composition lacks focus as a function.

His movie is additional hobbled when he begins together with the digitized and restored items that Hesse shot (in a way “The Eyes of Ghana” is a well-meaning promoting for additional funds to revive the remainder of Hesse’s saved footage). Not as a result of the photographs aren’t distinctive, as a result of Hesse’s movies are so significantly better than the film we’re watching, which depends on a garish Disney-esque rating by Kris Bowers and an on-the-nose need to seize Hesse at such an angle that we’re at all times staring deeply into his eyes. Although Proudfoot clearly has an appreciation for the fabric—“Rwanda and Juliet,” his solely different function, thought of the post-genocide lives of that African nation—this movie is just too slick and too broad for such a delicate story.

The historical past of Vesuvius, whose eruption led to the decimation of Pompeii, has served as a shot that continues to be heard around the world. So when Gianfranco Rosi’s beautiful, black and white shot documentary “Under the Clouds” fixes its lens on the mountain, you instantly anticipate his movie will hyper give attention to that looming risk. However Rosi, whose earlier movies embody overtly political works like “Fire at Sea” and “Notturno,” not often takes discover of the life contained in the volcano. He as an alternative weaves by means of the peculiar life bustling round Naples and the recording of lives gone passed by the archeologists excavating native historic websites.

“Under the Clouds” isn’t a talky documentary, per se. It’s completely observational. Even so, Rosi’s meditative lens takes discover of the chatter emanating from its many places. There’s the emergency name heart the place folks cellphone for help following each tremor. Whilst you’d assume these can be intense communications, their inherent franticness is minimize down by the humor and sweetness of the officers taking these calls. Larger chatter is discovered by way of Syrian boatmen on the lookout for entry into the port for his or her Ukrainian grain. And much more speak happens each time we soar into the work carried out by archaeologists, who’re navigating, at occasions, huge tunnels and excavated caverns holding the frozen, calcified victims of Pompeii.

When mixed, all of those scenes entail a documentary fascinated by the fragility and suspension of life. The rhythmic enhancing, for example, creates a round sample, returning to and remixing pictures whose continuous convergence imbues these mundane pictures with nice which means. Rosi additionally ventures right into a film home, the place he performs movies like “Final Days of Pompeii” (1913) and “Voyage to Italy” (1954), which converse to the long-held cultural fascination with an occasion that continues to fascinate outsiders and stays ever prevalent within the minds of these dwelling close to the famed volcano. In a way, by locking his up to date documentary on this wealthy black and white images, Rosi has additionally put his movie alongside these. Thereby, preserving the artifacts of reminiscence that make this place residence.