In Might of 2025, Jafar Panahi gained the Cannes Movie Pageant’s highest honor, the Palme d’Or, for his movie “It Was Just an Accident,” a stark drama about a number of former prisoners who debate whether or not to kill a person they imagine tortured them after they have been inmates. Fairly surprisingly, the federal government of Iran really allowed Panahi to go away the nation and attend the pageant. When he returned to Tehran, I learn, one of many first issues he did was to go to the grave of Abbas Kiarostami. The gesture was altogether acceptable: Not solely was Kiarostami the one Iranian director to have beforehand gained the Palme d’or (for “Style of Cherry” in 1997), he was additionally Panahi’s mentor; the 2 had a creative relationship that spanned many years previous to Kiarostami’s demise in 2016.

“It Was Simply an Accident” has been successful awards and audiences world wide since Might and is now thought of a number one candidate for a number of Oscar nominations. However Panahi’s highway to this juncture has not been straightforward. On the New York Movie Pageant in October, he advised Martin Scorsese that when he noticed his film premiere at Cannes, it was the primary time he had watched one among his movies with an viewers in 17 years – a hardship that the majority filmmakers can scarcely think about. Since 2010, the Iranian regime has imprisoned him, banned him from making movies, writing screenplays and giving interviews, and prevented him from leaving the nation. But he has endured, making low-budget movies with out official permission and smuggling them in another country to overseas festivals. “Accident” is the sixth such movie he’s made because the authentic ban was handed down.

The restrictions Panahi has labored below clearly have an effect on the world’s notion of him. Most filmmakers, after they launch a significant work, spend a 12 months or extra on the highway: attending festivals, talking with audiences, doing publicity, giving numerous interviews. That Panahi has been unable to any of this has, I imagine, inevitably meant that his work previous to “Accident” is much less well-known than it deserves to be. Rectifying that was one among two targets I had in programming the pageant “Panahi & Kiarostami: Two Masters” (Jan. 2-8 on the IFC Middle in New York). The opposite purpose was to position Panahi’s profession within the context of Iranian cinema, particularly the essential relationship with Kiarostami.

From a historic perspective, the filmmakers signify the 2 nice eras of Iran’s cinema: the pre-revolutionary and the post-revolutionary. Beginning in 1970, 30-year-old Kiarostami started making brief movies, primarily about youngsters, for the government-sponsored Middle for the Mental Improvement of Kids and Younger Adults. He honed his craft throughout these years, but the movies, and two options he made within the Seventies, reached few audiences outdoors Iran. After the 1979 Iranian Revolution, nevertheless, the federal government of the Islamic Republic got down to revive the nation’s cinema, and Kiarostami was one of many pre-revolutionary administrators invited to renew working. His first post-revolutionary characteristic, “The place Is the Good friend’s Home?” (1986), a couple of rural schoolboy’s effort to return a pal’s pocket book, took a number of awards on the Locarno Movie Pageant, launching Kiarostami internationally. His third characteristic, “And Life Goes On” (1992), concerning the aftermath of a devastating earthquake, was taken up by Cannes, the place he started getting important consideration in earnest.

Though different Iranian filmmakers have been much more celebrated within the early post-revolutionary interval, Kiarostami was evidently on Panahi’s thoughts from early on. After serving within the Iran-Iraq conflict after which making a number of brief documentaries, he directed his first narrative brief, “The Good friend” (1992), as a tribute to Kiarostami’s first brief, “Bread and Alley.” Not lengthy after, he referred to as and left a message on Kiarostami’s answering machine expressing admiration for his movies and a want to work with him. Simply starting to work on “By way of the Olive Timber” (1994), concerning the making of “And Life Goes On,” Kiarostami invited Panahi to affix him; Panahi is seen within the movie appearing as assistant director.

One thing much more vital for Panahi’s profession, although, occurred throughout this shoot. He had an thought for a characteristic, and Kiarostami not solely appreciated it however provided to write down the script, dictating pages as they drove to and from the set. Though the movie, a couple of woman’s effort to purchase a goldfish for her New Yr’s celebration, fell into the Kiarostami-initiated style of child-centered movies, it was totally different in a single respect: not like his movies, it centered on a woman. Panahi discovered one named Aida Mohammadkhani, who gave a outstanding efficiency within the position; the movie additionally demonstrated his abilities supervising enhancing and cinematography.

“The White Balloon” (1995), Panahi’s characteristic debut, grew to become the primary post-revolutionary movie to win a significant worldwide prize, Cannes’ Digital camera d’Or for finest first movie. It was additionally the primary Iranian movie to develop into a worldwide art-house hit, and in Japan it gained a prize that carried a big money award with it. In contrast to Iranian administrators who “climbed the ladder” by making movies that obtained Iranian recognition earlier than reaching world audiences, Panahi had a really profitable worldwide profession from the primary.

With Kiarostami’s second post-revolutionary characteristic, “Shut-Up” (1990), an interesting docudrama a couple of poor man arrested for impersonating the director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, the director had successfully inaugurated one other de facto Iranian style: movies about filmmakers and movie’s social affect (together with class variations). He prolonged the style with the next dramas “And Life Goes On,” a couple of movie director attempting to find if the children who acted in his earlier movie survived an earthquake, and “By way of the Olive Timber,” concerning the making of the earlier movie. (Critics dubbed these two movies and the sooner “The place Is the Good friend’s Home?” The Koker Trilogy, for the village the place a lot of their motion is about.)

For his follow-up to “The White Balloon,” Panahi began out with a premise that appeared like one other Kiarostami-esque kid-on-a-quest story: when nobody reveals as much as acquire her after faculty, just a little woman units off throughout Tehran on her personal to seek out house. Halfway via the story, nevertheless, one thing occurs: the kid actor (Aida Mohammadkhani once more) declares she’s sick of filming, takes off her mic, and darts out into town. Thus does “The Mirror” (1997) out of the blue morph right into a Kiarostami-esque self-reflexive story about filmmakers and filmmaking (enjoying the director, Panahi seems within the movie, a lot as Kiarostami and Makhmalbaf did in “Shut-Up.”) However this may be the final time critics might regard Panahi’s work as “faculty of Kiarostami.”

On reflection, it appears that evidently the late ‘90s introduced a darkening temper to Iranian cinema, and Kiarostami – by then that cinema’s main determine internationally – was prepared to go away behind each lyrical movies about youngsters and witty, complicated “meta” tales about filmmakers and filmmaking. “Style of Cherry,” the movie he despatched to Cannes in 1997, was one thing stark and new: the story of a person motoring round Tehran looking for somebody who will assist him commit suicide. Though he seems to be a well-off skilled, we’re advised nothing about the primary character’s life or why he would wish to finish it. However neither does the movie inform us that life in post-revolutionary Iran was not the rationale: all the things, together with the character’s final destiny, is left to the viewer’s creativeness.

In my e-book Within the Time of Kiarostami: Writings on Iranian Cinema, I word that once I first encountered Iranian movies within the early ‘90s, I half anticipated to discover a dissident cinema, like among the movie and literature from the Soviet Union previous to 1989. What I discovered as a substitute have been buoyant movies about children and intelligent, subtle movies about filmmaking (extra like Russian movies of the ‘20s, when the spirit of revolution was nonetheless within the air). For my part, “Style of Cherry,” which divided critics however gained the Palme d’Or at Cannes, was the movie that didn’t announce, however slightly signaled, a pivot towards dissidence.

Nonetheless, what was arguably implicit in Kiarostami’s movie grew to become fairly specific in Panahi’s third characteristic. “The Circle” (2000) is a really hanging and daring movie. Following the tales of 4 girls (grown-ups, not children), it makes clear the cruel restrictions and forces that delimit the lives of Iran’s feminine inhabitants below the Islamist regime. The movie’s ingenious use of sound and its diverse visible language display Panahi’s abilities as a stylist. Upon completion, and with out the permission of the Iranian authorities, “The Circle” was despatched to the Venice Movie Pageant, the place it gained the Golden Lion. It was banned in Iran.

In talking of “The Circle,” and lots of movies afterwards, Panahi stated that he’s not a political filmmaker, however slightly an artist who makes movies about social topics. In any case, it’s price noting that the truth that he had a global viewers and backers meant that he was within the uncommon place for an Iranian filmmaker of with the ability to make movies that have been more likely to be saved from home distribution. That issue led some girls to cost that the movie’s narrative entails distortions meant to reflect the prejudices of overseas viewers.

For his subsequent movie Panahi returned to collaboration with Kiarostami. A real-crime story, “Crimson Gold” (2003) begins in an upscale jewellery retailer the place apparently a homicide and a suicide happen; the movie then flashes again to point out what led to this juncture. Kiarostami wrote the screenplay based mostly on a information merchandise he had learn. Panahi’s assured path emphasised realism in its depiction of each the prison underclass and the rich in Tehran. The result’s a really pointed and authentic movie on a topic of curiosity to each Kiarostami and Panahi: class inequities in post-revolutionary Iran.

“Offside” (2006), Panahi’s subsequent movie, returned to the topic of “The Circle,” feminine oppression, however with a tone that was a lot lighter and that depicted girls’s company and resistance. The premise: a gaggle of younger women disguise themselves as boys to sneak into Azadi Stadium to see a World Cup playoff match. (Iranians are enormous soccer followers, however after the Revolution, the regime banned girls from attending matches to maintain them from seeing males in shorts and tight-fitting shirts, and to forestall the blending of sexes.) Panahi submitted a faux script to acquire permission to shoot the movie, which was executed in precise matches. Towards the tip of filming, the federal government tried to close it down however the challenge was accomplished and the movie premiered on the Berlin Movie Pageant. (Twenty years later, the “open stadiums” motion in Iran continues.)

In some ways, the Nineteen Nineties in Iranian cinema belonged to Kiarostami because of the broad acclaim earned by the 5 options he launched throughout the decade, culminating with “The Wind Will Carry Us” (1999), a prize winner at Venice however the final celluloid characteristic he shot in Iran (thereafter he turned to low-budget digital documentaries and experimental movies and two options he made outdoors Iran). The subsequent decade, the primary of the brand new century, was, within the largest sense, Panahi’s: “The Circle,” “Crimson Gold” and “Offside” confirmed him on the top of his powers as a storyteller and stylist in making full-scale dramatic options. However all three movies have been banned in Iran, establishing an oppositional relationship between Panahi and the regime that might drastically complicate his life and artwork within the subsequent decade.

In July of 2009, protests broke out throughout Iran after the disputed re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Panahi was arrested close to the grave of Neda Agha-Soltan, a younger lady who had been gunned down throughout the protests. He was capable of contact mates and fellow filmmakers, and their stress helped safe his launch. Nonetheless, on March 1, 2010, his house was raided by police and Panahi, his spouse, daughter and 15 mates have been arrested and brought to the notorious Evin Jail. Most have been quickly launched, however not Panahi. His arrest sparked wave after wave of protests within the Iranian movie group and world wide. In New York, I joined with a number of mates to prepare a petition by distinguished American moviemakers demanding his launch. He was lastly launched on bail in late Might. (His struggles with the regime all through this era have been shared by his pal Mohammad Rasoulof, who needed to depart Iran to finish his 2024 movie “The Seed of the Sacred Fig.”)

Having seen the Iranian authorities again off from conditions after it obtained huge worldwide dangerous publicity, I assumed Panahi would obtain a slap on the wrist at most. So I used to be shocked when he went to trial in December, 2010, and, convicted of “propaganda in opposition to the Islamic Republic,” was sentenced to 6 years in jail and 20 years of not making motion pictures, writing screenplays, giving interviews or leaving Iran. The next October, a court docket upheld the ban however the jail sentence was changed by home arrest.

I’m unsure why the ban on Panahi’s journey was lifted in 2025, however in December, after he had been selling “It Was Simply an Accident” internationally since Cannes, an Iranian court docket sentenced him in absentia to at least one 12 months in jail and a two-year journey ban for “propaganda actions” in opposition to the regime. Did the authorities suppose this sentence would persuade him to keep away from Iran and settle out of the country, as different Iranian administrators have? In that case, they missed their mark. Panahi introduced that he would return to Iran after the upcoming Oscar season concludes.

Sentenced to twenty years of not making movies, Panahi reacted as you may count on: by persevering with to make movies – albeit in semi-secrecy, with minimal budgets and with out the official permissions that Iranian options are imagined to have. His subsequent 5 movies prolong the Kiarostamian custom of movies about filmmaking and filmmakers; Panahi stars in all of them. It’s noteworthy that as they progress, the movies widen the director’s geographical purview: from being confined to his house, to a secluded villa on the Caspian Sea, to a wide-ranging tour of Tehran’s streets, to highways and landscapes in northwestern Iran.

“This Is Not a Film” (2011), one among Panahi’s wittiest works, reveals that his spirits weren’t about to be dampened by the federal government’s draconian punishments. As such, the home made doc is a mirthful and exuberant act of defiance. Aided by filmmaker Mojtaba Mirtahmasb, Panahi reveals himself discussing his authorized case on the telephone, speaking about cinema and his future plans, and demonstrating the capability of latest digital know-how to permit an artist to create a whole characteristic at house. As soon as accomplished, the not-a-film was smuggled out of Iran on a USB drive and premiered on the 2011 Cannes Movie Pageant; it was subsequently distributed worldwide and shortlisted for the Documentary Oscar.

“Closed Curtain” (2013) is just like the flipside of the earlier movie: dramatic slightly documentary and depressive slightly than defiant. I as soon as described a Kiarostami movie as “Rossellini twined with Pirandello,” and this movie reveals the same conjunction. Co-directed by Kambozi Partovi, it begins out depicting three characters taking refuge in a home on the Caspian Sea, then midway via comes a “coup de cinema” like that in “The Mirror”: Panahi himself seems and the movie shifts into what I referred to as in my review “a form of subjective surrealism – name it a documentary concerning the inside Panahi’s head lately.” The movie gained Panahi the Silver Bear for Finest Script on the 2013 Berlin pageant.

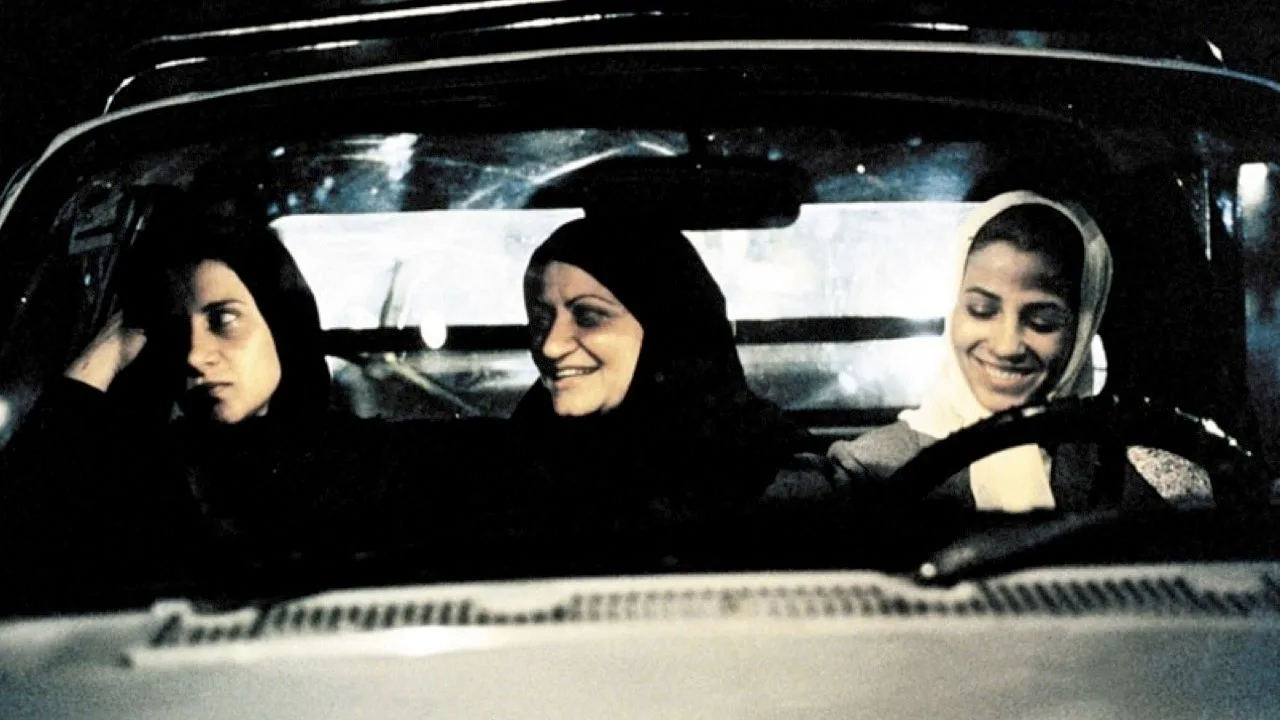

“Taxi” (2015). Anybody who’s visited Tehran is aware of how its streets are like an unlimited dramatic-comedic stage for the zany tradition of taxis (typically shared) and taxi drivers. On this pseudo-documentary, Panahi performs a taxi driver and will get a variety of self-evident pleasure not solely from his freedom to roam across the metropolis but additionally from the tales and observations he elicits from his passengers. The movie gained Berlin’s prime prize, the Golden Bear.

“3 Faces” (2018) continues Panahi’s arguments in opposition to the remedy of girls below the Islamic Republic whereas paying tribute to a few era of Iranian actresses – and would-be actresses. Beginning out with an obvious video suicide word from an aspiring younger actress, the movie then sends Panahi and real-life actress Behnaz Jafari on a highway journey throughout northwestern Tehran in the hunt for the woman’s destiny. Once I noticed Panahi in Tehran in 2017, he advised me he couldn’t make the movie until he discovered a feminine star; fortunately, Jafari was courageous sufficient to take the position. Once I noticed him in early 2018, he hoped the regime would let him go to Cannes to premiere the movie. That didn’t occur, however the movie gained the Finest Screenplay award for Panahi.

In “No Bears” (2022) the story finds Panahi on Iran’s border with Turkey directing a movie by video distant about Iranians wanting to flee to Europe. However the greatest battle he faces comes within the rural village the place he’s staying. Writing about the film’s U.S. debut on the 2022 New York Movie Pageant, I stated, “Greater than his different current movies, ‘No Bears’ reveals the affect of Panahi’s mentor, Abbas Kiarostami, particularly the Kiarostami movies ‘By way of the Olive Timber’ and ‘The Wind Will Carry Us.’ However maybe most important is that, slightly than impugning the Islamic Republic, Panahi, like Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf earlier than him, is interrogating the deep constructions of Iran’s pre-modern, non-urban tradition. The villagers’ antiquated morals and worldview, he implies, are what’s imprisoning them, not any political strictures.”

Whereas all 5 of those current movies are fascinating and worthy of consideration, “This Is Not a Movie” and “No Bears” have my vote as this era’s important masterpieces.

The Palme d’Or-winning “It Was Simply an Accident” (2025) was his sixth movie made with out authorities approval, and it differs from its predecessors in sure respects, together with that Panahi doesn’t seem in it. I’ll ask him why that is after we focus on his profession and its relationship to Kiarostami’s work on the IFC Middle on Jan. 5.

Extra than simply representatives of two totally different generations and eras of Iranian cinema, Kiarostami and Panahi had totally different personalities and creative goals. Kiarostami’s work was typically referred to as poetic and philosophical; an completed poet, artist and photographer, he made movies that have been steeped within the influences of Iran’s historical literary and creative traditions, but additionally encompassed modernist and postmodern tendencies. Panahi’s work was extra easy, centered on stylistic potentialities and present social realities, particularly the challenges confronted by girls. From the primary, Kiarostami was an experimenter and an innovator, particularly within the genres of child-centered movies and movies about cinema itself. He blazed trails that others adopted, none extra assiduously or inventively than Panahi, whose homages prolonged and paid eloquent tribute to the significance of his mentor’s work.

Descended from the instance of Italian neorealism, each administrators have been passionate concerning the cinema’s potential for therapeutic the injuries of a society riven by age-old poverty and trendy revolution and violence. Each gained worldwide reputations and relied on overseas audiences for the continuance of their careers, but neither elected to maneuver out of Iran, as Makhmalbaf, Bahram Beyzaie and others did. Kiarostami had movies banned, however he was in Italy making “Certified Copy” when the “stolen election” that returned Ahmadinejad to energy provoked protests that swept Panahi into the beginnings of his lengthy battles with the present Iranian regime.

Having hung out with each Kiarostami and Panahi, I keep in mind each for the irrepressible ebullience of their personalities. At any time when misfortunes or government-decreed hardships got here their approach, their reactions have been often grins, laughter and joking. Luckily Kiarostami by no means went to jail. Panahi went, again and again, however has by no means wished to say a lot concerning the cruelties that have been visited upon him and his household, or concerning the techniques, together with starvation strikes, that he was compelled to undertake to outlive and achieve launch.

I contemplate the braveness and fortitude Panahi has displayed via these ordeals to be completely extraordinary. Cinema might have a variety of masters on the extent of Kiarostami and Panahi, however when has there ever been one who has been subjected to the extended hardships that Panahi has endured? That he’s nonetheless decided to return to Iran and one other jail sentence after the Oscars makes him appear akin to leaders like Vaclev Havel and Nelson Mandela, whose braveness pointed towards a greater day for his or her nations.

Panahi and Kiarostami Movies: Vital Pairings.

Once I proposed this collection, I recommended that the movies of Panahi and Kiarostami be grouped in pairings that may provide insights into among the connections between the 2 administrators’ work. Whereas the IFC Middle will not be capable of current these movies as double options, I nonetheless hope viewers may consider them as “in dialog” with one another.

Childhood’s Challenges

“The place Is the Good friend’s Home?” is the lyrical comedy-drama that prolonged Kiarostami’s prer-evolutionary movies about children into the post-revolutionary period. He additionally scripted “The White Balloon,” Panahi’s extremely profitable characteristic debut which incorporates a great efficiency by little Aida Mohammadkhani.

Soccer Fever

In Panahi’s dramatic and infrequently hilarious “Offside,” feminine soccer followers disguise themselves as boys to get right into a World Cup playoff match. The Iranian obsession with the game additionally figures into Kiarostami’s “And Life Goes On,” the place a World Cup broadcast airs as a movie director and his son motor via an earthquake’s current devastation.

Cinema Captives

Arguably the best of all Iranian movies, Kiarostami’s “Shut-Up” paperwork the trial of a person arrested for impersonating a well-known movie director. A tribute to a few generations of Iranian actresses, Panahi’s “3 Faces” is a highway film that factors up each the significance and the difficulties confronted by feminine performers in Iran’s cinema.

Panahi’s Presence

Panahi performs Kiarostami’s assistant director in “By way of the Olive Timber,” an acclaimed movie concerning the making of a earlier movie. He reappears as himself in his personal “This Is Not a Movie,” enjoying a director making a movie after being banned from making movies.

Darkish Dramas

Kiarostami’s Palme d’Or winner “Style of Cherry,” a couple of man looking for assist in committing suicide, appeared to sign a darkish flip in Iranian cinema. It could have impressed the acerbic tone of Panahi’s “The Circle,” which depicts the troublesome lives compelled on 4 girls by situations within the Islamic Republic.

Rustic Realities

Each Panahi’s “No Bears” and Kiarostami’s “The Wind Will Carry Us” present their protagonists confronting rural realities whereas taking pictures movies/movies in far northwestern Iran. The movies intensify the backwardness of the place, however whereas Kiarostami makes use of the setting to assemble an allegory about poetry, Panahi muses on the prices of ignorance.

Tehran Excursions

Panahi’s “Taxi” and Kiarostami’s “Ten” largely happen in vehicles motoring round Tehran. (Each administrators loved driving within the metropolis.) In Panahi’s movie, he’s the genial taxi driver. In “Ten,” it’s a soccer mother nicely performed by Mania Akbari. Each movies have a robust documentary component and concentrate on the drivers’ interactions with passengers.

Poverty’s Value

The struggles of Iran’s underclass are depicted in Kiarostami’s pre-revolutionary debut, “The Traveler,” a couple of village boy who cheats his buddies to get cash to attend a soccer match in Tehran, and in a true-crime drama he wrote for Panahi to direct, “Crimson Gold,” concerning the plot to rob an upscale jewellery retailer.

Surreal Surprises

Panahi’s “Closed Curtain” and Kiarostami’s “Licensed Copy” each have narrative twists about halfway via that evoke surrealism. In Panahi’s drama, the shift entails his view of his personal predicament. In Kiarostami’s, it considerations the character of the connection between a married couple performed by Juliette Binoche and William Shimell.

On Sunday, January 4, at 1:15pm, following the 11:30am screening of “By way of the Olive Timber,” I’ll reasonable a panel about Panahi and Kiarostami’s work that may even embrace Prof. Jamsheed Akrami, historian and author Arash Azizi, movie professor and former New York Movie Pageant head Richard Pena, and critic and translator Leslie Camhi.

On Monday, January 5, Jafar Panahi and I’ll focus on his work after the 6pm screening of “By way of the Olive Timber.” And he’ll introduce the 8:35pm screening of “This Is Not a Movie.”