In Korean, there’s a customized referred to as 삼년상 (phonetic spelling/pronunciation: sam-nyun-sang). Again within the days of the Joseon dynasty, when a family’s father handed away, it was customary for grownup youngsters, even after the funeral, to construct a shack close to the burial website and stay there for at the very least three years. It represents a means for a kid to repay their dad and mom for the primary three years, once they have been helpless with out their dad and mom’ assist. One might actually nonetheless grieve after three years in the event that they wished, however there was a minimal expectancy of how lengthy somebody ought to mourn.

I discover it fascinating that in Korean tradition, there’s a built-in “naked minimal” for unhappiness; there’s a linearity to anguish and grief that’s embedded within the language itself. I considered this idea whereas watching director Park Chan-wook’s newest, “No Other Choice,” an acerbic and farcical black comedy made for this period of mass layoffs, quiet quitting, and a crumbling job market.

Lee Byung-hun, in a welcome change from the action-hero roles he’s finest recognized for to Western audiences, performs the well-meaning and constant Man-su, a longtime worker of the paper firm Photo voltaic Paper. When he’s unceremoniously fired from his job (“You People say that to be fired is to be ‘axed?’ [In Korea we say] off together with your head!” he says, highlighting cultural variations in how one’s vocation is intimately tied to 1’s self-worth), his sense of id crumbles. When he sees the burden of being unable to financially present for his spouse, Lee Mi-ri (Son Ye-jin), and his youngsters, Si-one (Woo Seung Kim) and Ri-one (So Yul Choi), he hatches a brutal plan to regain his pleasure: remove the opposite job candidates for the place that he’s gunning for.

In fact, the irony of the movie’s title is that Man-su has many different selections than homicide. Somewhat than flip his frustrations in direction of the techniques preying upon individuals like him, he harms these he might as a substitute be in group with, and his stubbornness to work in a single particular space corrupts his creativeness, stopping him from contemplating different methods of provision.

“The good tragedy of this movie is that his rage shouldn’t be aimed on the proper goal; he factors his gun at people who find themselves his double, these identical to him, these he ought to empathize with essentially the most, as a substitute of the corporate that fired him in a single stroke, even after he toiled there for 25 years,” Director Park shared.

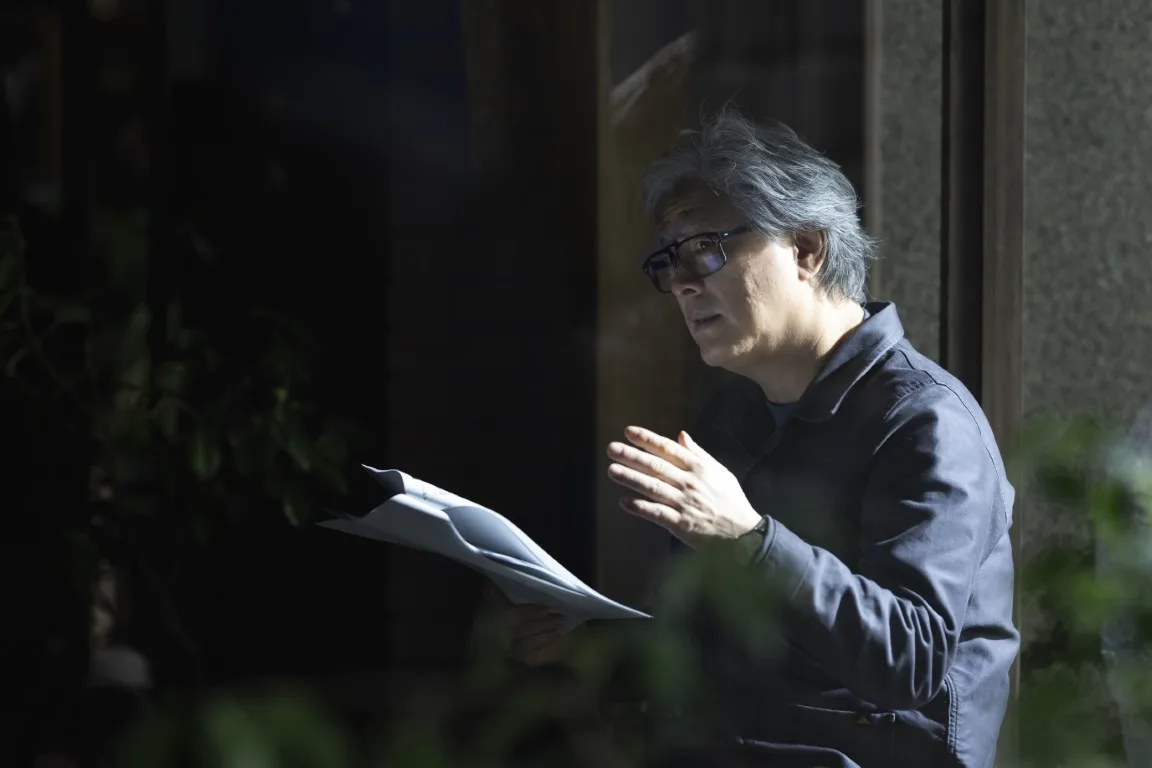

Over Zoom, Park and Lee, whose phrases have been graciously translated by Ji-won Lee and Isue Shin, spoke to RogerEbert.com individually; this piece combines their interviews into one, fluid dialog. They unpacked the deadly foolishness of Man-su’s campaign, how the movie’s interaction of sunshine helps us perceive the characters’ interiority in a given scene, and the way engaged on the venture has reshaped their relationship to disappointment and failure.

This dialog has been edited and condensed for readability.

Director Park, there’s a palpable anger that programs by way of your tasks, out of your aptly titled Vengeance trilogy to the romantic disquietude of “Decision to Leave.” I’m curious should you view filmmaking as a vessel for holding the trend you’re feeling in regards to the world, and the way that’s developed for you as a filmmaker?

PC: Actually, the flicks I’ve made prior to now–as you talked about–portrayed that feeling of rage in nice element, however for this movie, I needed to take the alternative method from my previous work. Man-su’s rage is captured in a single line within the movie, the place he says [paraphrased] “You bossed me round for 25 years.” He might have his frustrations in direction of the corporate or the capitalist system, however as a result of he’s pondering realistically about his life, he accepts his incapability to vary them in some respects. He accepts the truth that he’s residing in and as a substitute tries to be pragmatic about his targets and advantages, which leads him to suppose that if he needs to get his job again, he has to kill different individuals.

What’s unhappy is that the targets that he tries to remove usually are not the targets of his rage or the progenitors of his ache. These are individuals in a state of affairs just like his. He ought to have the ability to perceive them and be mates with them. The good tragedy of this movie is that his rage shouldn’t be aimed on the proper goal; he factors his gun at people who find themselves his double, these identical to him, these he ought to empathize with essentially the most, as a substitute of the corporate that fired him in a single stroke, even after he toiled there for 25 years. That’s the place foolishness is available in as nicely: he sees the people who find themselves identical to him as his targets. He can’t consider another strategies and has failed to search out a substitute for regain the boldness and respect he has as a father and husband.

The entire candidates ought to have as a substitute teamed as much as take down the system. Your response jogs my memory of a scene the place Man-su’s first goal, Goo Beom-mo (Lee Sung-min), is so annoyed that he rolls round exterior, screaming silently. The expression of our agony at all times needs to be palatable, however actually, typically all we need to do is scream unceremoniously.

PC: Even in that scene, Beom-mo needs to cry out loud, however is apprehensive his spouse would possibly hear him, so he has to carry it in as a lot as potential. He has to ration out his moans; I believe that makes him extra sympathetic. You’re feeling unhealthy for him as a result of he appears to be like so pathetic. In any case, he has to do this.

Lee Byung-hun, throughout tasks like “The Good, the Dangerous, the Bizarre,”” Emergency Declaration,” “Concrete Utopia,”… you’ve had the chance to play a really specific model of Korean masculinity. Your position as Man-su in “No Different Alternative” complicates that. Are you able to communicate to how your method to taking part in patriarchal figures has developed all through your profession or the way you view these roles in dialog?

LB: Man-su is simply an odd man. His major purpose is to guard his household, and that’s one thing I relate to; I may not have the identical life as him, however initially, the entry level to empathy wasn’t tough. What was tough was the extremity of those conditions Man-su finds himself in; my thoughts shouldn’t be like his, so in attempting to come up with who he’s, I needed to first perceive that these usually are not “odd choices.” Comprehending that, understanding that somebody who isn’t just like me can then be pushed in such a approach to make these extreme selections, to personal that was the really tough half.

Versus Man-su’s specific model of masculinity, as a result of I used to be born and grew up in Korea, I do perceive his embodiment of patriarchy. I believe that, due to this period of globalization and the extra constant trade of cultures, we transfer collectively extra simply relating to cultural adjustments. A number of the macho spirit and male chauvinism that defines Korean males, I believe, has largely disappeared. There are nonetheless traces of it, although; it’s not at all times overt, and so taking part in a personality who’s “modernly masculine,” for whom these footprints of toxicity stay, was an fascinating problem.

Yeong-tak, your character from “Concrete Utopia,” has shades of Man-su, since each view their sense of provision as deeply tied to homeownership.

LB: I believe each are very Korean tales in that respect. In “Concrete Utopia,” even within the aftermath of devastation, individuals’s sense of safety is so deeply tied to residence possession, and the safety of household comes from nurturing inside that residence. It’s fascinating to deal with these concepts, however with completely different filmmakers.

Director Park, I’m struck by the spectre of Man-su’s father; he occupies the movie as a form of illusion, who leaves behind not only a gun, however specific narratives round what it means to be a supplier and a person to his son. By way of the method of adapting Donald Westlake’s novel, did it supply you a chance to mirror on the acquainted narratives you have been raised with (and which of them you needed to both settle for or reject)

PC: (Laughs) I wasn’t fairly the insurgent to my dad and mom, however I additionally wasn’t somebody who obeyed every little thing they stated or advised me to do.

I just like the perception about how Man-su’s father is sort of a ghost within the movie, that he’s lingering and flickering within the background; he’s part of the film, however he’s unseen. There was by no means a plan to depict Man-su’s father within the movie, but when it weren’t for Man-su’s father’s gun, which Man-su noticed repeatedly day in and time out, Man-su may not have ever deliberate these murders within the first place. Murdering your competitors is a silly thought within the first place, however the presence of a firearm enabled Man-su to behave.

I believe Man-su was attempting to be completely different from his father. Whereas his father raised and killed pigs, I believe that motivated Man-su to turn out to be a lover of vegetation. On high of that, Man-su dismantled the storage his father had used to hold himself in and as a substitute constructed a greenhouse. He needed to stay his life in another way from the way in which his father did.

But within the scene the place his son, Si-one, is taken by the place, Man-su quotes his personal father’s phrases to his son. He’s principally telling his son to make a false assertion to the police, and in doing so, is passing down trauma and historical past that he didn’t need to inherit from his father within the first place. What Man-su didn’t need to inherit from his dad, he inherited anyway, and he additionally handed the identical vice right down to his personal son.

I’ll preserve a watch out for “No Different Alternative 2” that follows Si-one’s violent escapades. Lee Byung-hun, I used to be struck by a line A-ra says to Beom-mo: “It’s not the truth that you misplaced your job; it’s the way you dealt with it.” Disappointment and rejection appear par for the course when working within the movie business; has engaged on the venture supplied you an opportunity to mirror on the way you course of moments of loss?

LB: (Laughs) Are you saying that now if I expertise hardship, I ought to simply do away with my rivals?

I imply, I’m not not saying that …

LB: I believe actors study lots by way of the characters that they play, and it additionally causes them to typically change their very own opinions. With any character I’ve embodied, my ego and my full selfhood have been affected to a sure extent, and my worldview is consistently challenged. I believe that, for a lot of actors and even administrators and creatives who make artwork, when one venture ends, the subsequent job prospect may be very tentative, so many are at all times in a pseudo-state of joblessness. I believe I’ve been actually fortunate to be able to decide on my subsequent venture, however I do know many creatives are at all times in a limbo-like state.

To that time, although, even inside your profession, a job like “No Different Alternative” is particular since you get to flex extra of your comedic muscle mass.

LBH: I truly love the style of black comedy rather a lot. Even “Concrete Utopia,” I’d say, belongs to this style. The story may be very darkish and miserable, as it’s a catastrophe venture, however there are various ironic and humorous conditions. Lots of people have seen me in motion movies and likewise very severe dramas, and so, particularly to a Western viewers, it is likely to be new to see me in a extra comedic position.

Director Park, what you articulated about inherited trauma between Si-one and Man-su jogs my memory of one other line spoken by Lee Mi-ri: “For those who do something unhealthy, it means we’re in it collectively.” There’s a loyalty to the household you discover that’s each poisonous and protecting; I really feel like deconstructing the security of the household unit is a provocation that’s been a theme in your work.

Sure, that’s nice perception as a result of Mi-ri is somebody who doesn’t blame different individuals, and even when she has finished nothing improper herself, she nonetheless takes duty. Though she had no half within the murders her husband dedicated, she’s somebody who’s asking, “Did I play an element?” I actually did need to present this character’s maturity.

But should you look into it, the irony is that, maybe unknowingly, she had a extra direct position in what occurs than you’d suppose. She was the one who impressed the primary homicide as a result of she stated one thing akin to “I hope that particular person will get hit by lightning.” There’s additionally a time when she reminded Man-su that he was an alcoholic and nearly choked to demise on his personal puke, and that impressed the strategy for the second homicide.

Though she wasn’t deliberately doing so, she impressed the homicide twice. By way of this, I needed to indicate how intently interrelated this couple is and that one particular person’s wrongdoing isn’t just the person’s. Even when a person commits an act, it’s not solely that particular person’s duty. Everyone seems to be implicated.

Lee Byung-hun, I’m struck by Director Park’s use of sunshine within the movie. There are, after all, the blue mild of telephone screens, however I additionally consider the pure mild; the way it bathes the household within the opening scenes, the way it blinds Man-su in considered one of his interviews.

LB: Lighting is unquestionably such an enormous element of this venture and one thing that has deep that means with the story that Man-su goes by way of, as a result of the sunshine could be consultant of the difficulties, the hardships, and even the discomforts that the character might expertise. I needed to notice that for Director Park’s movies, even the smallest prop or department that’s distant holds that means. There are individuals on the crew who’re placing immense consideration to element into each ingredient. So whether or not it’s coloration or lighting, these elements have been all considered very meticulously.

The interview scene you talked about is one I really like lots as a result of it’s a second when Man-su is being harassed by all these parts of his surroundings. The lighting additional reinforces the sense that the world is out to get him, and it feeds into the frustration and desperation that later curdle into one thing worse.

I additionally need to point out the second the place Man-su is burying his final sufferer, and his spouse is holding the flashlight. The display screen splits in two; it’s a second of genius on Director Park’s finish to showcase the completely different mild sources guiding the characters, the substitute sources they use to light up their varied misdeeds, whereas they’re below the pure mild of the moon.

“No Different Alternative” is now in theaters by way of NEON.